Breaking gender norms: Women in chess

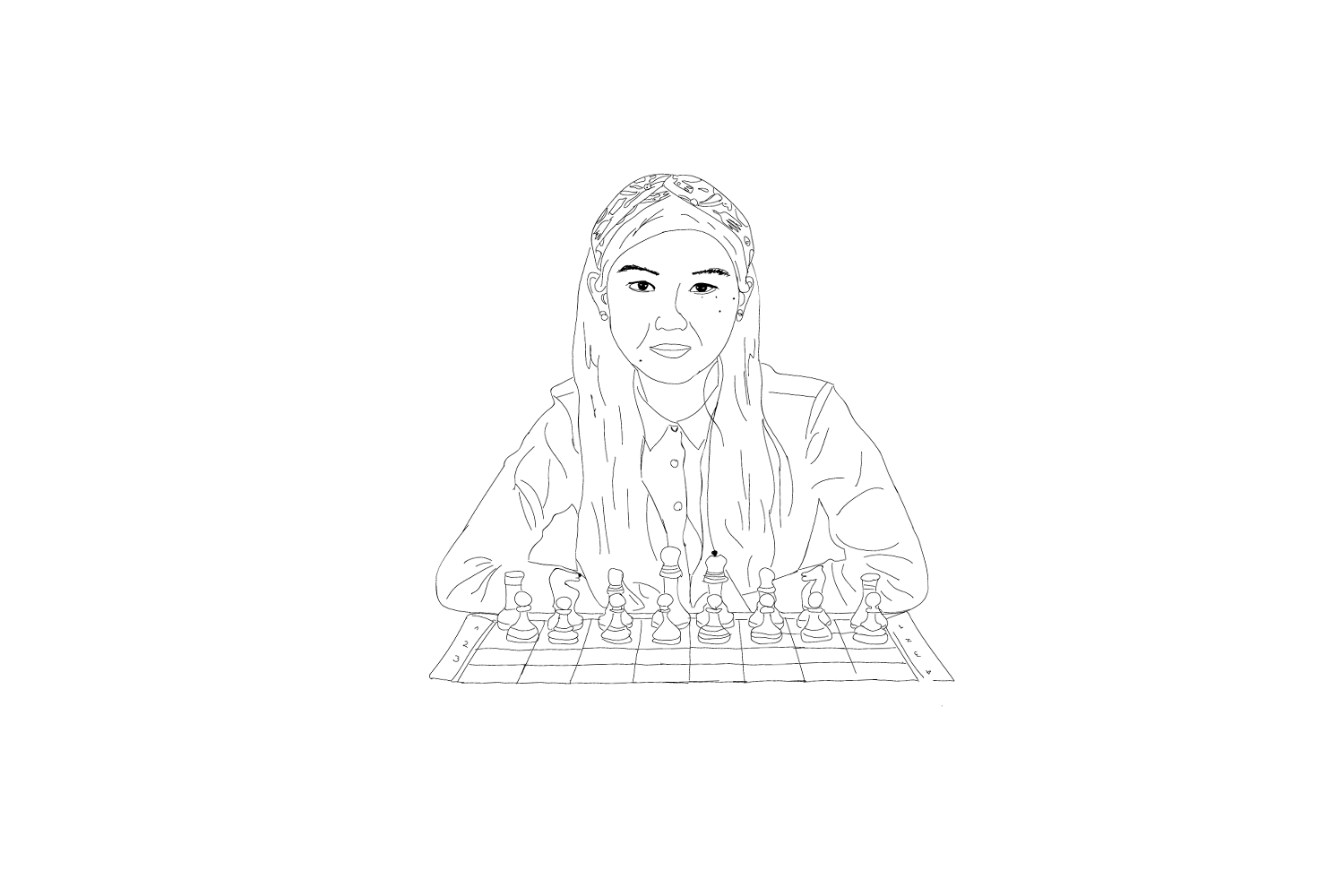

Breaking Gender Norms is a new column in which we start conversations with women who are challenging gender roles and defining what it means to be a woman in today’s workforce. This time we meet Woman Grandmaster Nomin-Edene Davaadembrel. The 20-year old is working as a full-time chess player in Hungary, where she spends her time advancing her chess abilities and encouraging young girls to engage in the world of chess by sharing her own story of success.

Born in Mongolia, Nomin-Erdene started playing chess at five-years-old after being introduced to the sport by her father. “I always enjoyed seeing my father playing chess. One day I set up the chess pieces correctly and from that day onwards my father encouraged me to play.”

Her interest grew by the day and she would use the sport as a tool to connect with the people around her, whether that meant playing against her grandfather or her father’s friends. “Looking back a long story begins here,” Nomin-Erdene says.

Three months later, at the first competition she ever participated in, she would go on to win a gold medal. This made her realise her potential and inspired her to focus her attention fully on chess. Turning her chess aspirations into reality became a priority which her parents supported.

Currently, there is only one female world chess champion, and there is generally a large performance gap between men and women in the sport. Nomin-Erdene does not think this has anything to do with the stereotype of women being less intelligent than men or the prejudice many female players face in the industry. Instead, she thinks this statistical gap is linked to women receiving less encouragement to pursue a career in chess than their male counterparts. She emphasizes that women are fully able to reach the world top, pointing to Judit Polgár, the female world champion, as a role model and example of what women are capable of achieving when they are given the chance.

Nomin-Erdene explains that to become a professional player, you need a change of lifestyle: doing chess full-time is almost an inevitable part of the process because it takes time and dedication to reach your potential. “My daily life is the same as for other professional athletes,” she says. On a daily basis, she spends more than six hours of training chess and an additional two hours of physical training.

While a high level of commitment is needed, making a living out of chess is difficult before you reach the world top. This becomes an even greater challenge for women, as they earn less than men in championships. The result is that many cannot afford to only focus on chess, thus entering an evil circle where there is a constant battle of the level of time you can afford to invest in your chess career. For people who have to find other work aside from chess, that means less time to put into improving skills and the world top being further out of reach.

Another issue that Nomin-Erdene points to is the expectations that come with the different genders. Women often find themselves in a position where they have to choose between chess and motherhood, while men who play chess are not expected to choose between the two in the same way. “Chess players face a long road to be a title-player such as International Master, Grandmaster. For females, it can be difficult to hold such a high level because of the time you have to put into it, which often does not coincide with motherhood,” she says.

Because of the many challenges women face on the journey to reach the top, Nomin-Erdene thinks women’s tournaments are an important stepping stone for women wishing to pursue a career in chess, providing them with more funds and confidence. “If women’s chess tournaments were more widespread, I think that would amount to a significant increase in women’s chess activity because they help encourage girls to focus on chess and see it as something possible to pursue.”

For the same reason, Nomin-Erdene thinks specific female titles are important, despite them simultaneously highlighting the divide between genders. “Women Grandmaster is an important title for women because it gives a pay-off for years of hard work and is a crucial part of proving their chess achievements.” She argues that such gender-specific titles have the purpose of making women more noticeable in the world of chess. In her opinion, women chess players achieving the title of Woman Grandmaster holds just as much status as men who become Grandmaster.

Women belong in the future of chess, but to build such a future where the gender gap is closed there needs to be a change of mindset. Nomin-Erdene believes that the most effective way to get girls engaged in the sport is with the help from the World Chess Federation and Women Chess Commission to “develop special missions for women’s chess groups and focus on the importance of community to inspire young women.” The future of chess lies not only in the hands of a society that needs to step away from traditional gender expectations – but it is also up to the influential chess organizations to put the gender gap on the agenda.

Related content

(Female) Skaters talk England’s skateboarding scene, 2020 olympics and the best thing about being female in a male-dominated sport.

Interview with the founder of Girl Power Meetups.

Fulfilling the Bechdel requirements does not make it an inherently feminist piece of fiction…

Exploring the dangers of not only fragile masculinity but the self-sacrifice associated with motherhood and womanhood.